Where did Belarusian Electronic Music Come From?

Experiments with electronic film scores and the first rave in Belarus.

Radio Plato has released a podcast called "Ikarus: Stories of Electronic Music in Belarus" created by the station's co-founder Aliaksandr Karneichuk, also known in the club scene circles as DJ KorneJ. Drawing on his years of experience in the craft of sound design, he has woven together a polyphonic narrative of Miensk's electronic scene of the 1990s. For this compelling piece of contemporary Belarusian cultural history to reach a wider international audience, we are publishing a text version of the podcast episodes in English. Belarusian-language text version is available on 34mag.net.

If you speak Belarusian and Russian, we highly recommend checking out the audio version of the podcast for full immersion. All you need to do is press play, close your eyes, and take a ride the old Ikarus bus through Miensk’s iconic nightclubbing spots of the era.

<iframe width="100%" height="450" scrolling="no" frameborder="no" allow="autoplay" src="https://w.soundcloud.com/player/?url=https%3A//api.soundcloud.com/playlists/1859530263&color=%23ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&show_teaser=true"></iframe><div style="font-size: 10px; color: #cccccc;line-break: anywhere;word-break: normal;overflow: hidden;white-space: nowrap;text-overflow: ellipsis; font-family: Interstate,Lucida Grande,Lucida Sans Unicode,Lucida Sans,Garuda,Verdana,Tahoma,sans-serif;font-weight: 100;"><a href="https://soundcloud.com/radioplato" title="Radio Plato" target="_blank" style="color: #cccccc; text-decoration: none;">Radio Plato</a> · <a href="https://soundcloud.com/radioplato/sets/ikarus-all-episodes" title="Ікарус: гісторыі электроннай музыкі Беларусі" target="_blank" style="color: #cccccc; text-decoration: none;">Ікарус: гісторыі электроннай музыкі Беларусі</a></div><h2>Preamble</h2>KorneJ: Whenever I read books or watch documentaries about the rise of electronic scenes in Chicago, London, Berlin, or Leningrad, I always find myself wondering what was happening in our parts at the dawn of the electronic music revolution? Who were the first Belarusian bands to start playing electronic music? What were first Belarusian raves like? And how did electronic music in general first permeate mass consciousness of the locals and contribute to the development of new cultural ties both within the country and with the outside world? These are the questions the first season of "Ikarus: Stories of Electronic Music in Belarus" attempts to answer.

To find out more about all of this I reached out to active participants of the scene: DJs, musicians, event organizers and journalists of the time. Among them are Alexi Kutuzov, Vadim Militsin, Zmicier Hryšanaŭ, Dasha Pushkina, Nikita Chudjakov, Mikałaj Miatlicki, Vladislav Buben, Vitali Harmash, Alena Barysik and Alaksiej Kustaŭ. I also found a wealth of media sources during my research: newspaper articles, radio broadcasts, assorted audiovisual materials on YouTube and music albums on streaming platforms. A few academic papers on related subjects helped me further structure my research and writing, among them Pavel Niakhayeu's unpublished paper, Volha Sasnoŭskaja's articles ("Nobody in This City Plays Such Music", "Healthy Dose of Extremism").

The first season of the podcast covers the period from the late 1980s to the early 2000s. During this period, the electronic scene came a long way from the first Non-stop Techno party in Dynama sports complex to big commercial open-air festivals with international stars on the line-up; from copying borrowed cassettes to clubbing-oriented online portals and discussion forums, labels and shows on national radio.

I specifically want to note that due to the wealth of the discovered materials, I've decided to focus mainly on stories from the electronic music scene in Miensk, the capital of Belarus and the main epicenter of cultural change. We may get into local scenes of other Belarusian cities further down the road, as there is no shortage of stories to be retold there as well. And of course, not all of the participants of those historic events were possible to reach for comment. I would thus consider this podcast as another piece of the puzzle rather than a comprehensive encyclopedia on the subject.

So let's start!

While Western Europe had the first electronic music studios affiliated with radio stations (such as those in Cologne, Paris, Berlin, and even Warsaw), in the USSR, innovative music technologies did not receive such recognition. The first recorded attempts to create Belarusian electronic music occurred in cinema. The thing is that film music was not considered an independent art form; it was perceived solely as expressive means of the cinema genre and therefore was less controlled by the Ministry of Culture.

In episode 426 of his Krakatuk show a Belarusian poet, broadcaster and musician Viktar Siamaška provides a comprehensive overview of this topic:

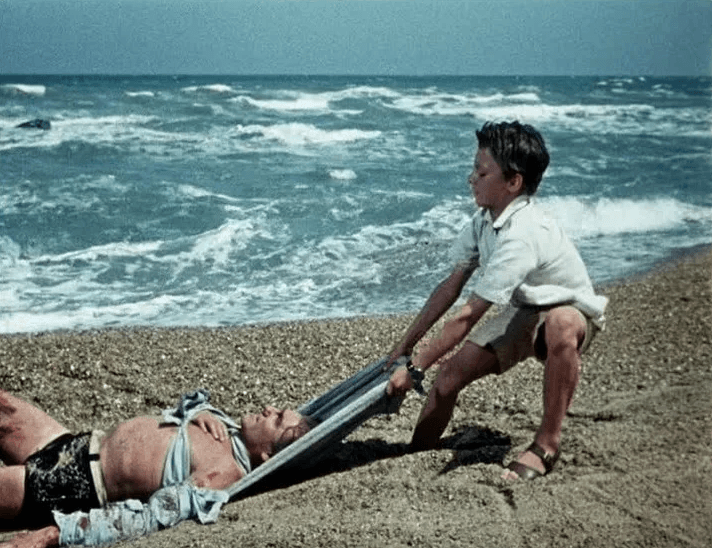

– Soundtrack of ‘Poslednij Diujm’ (The last inch), a color film from 1958 based on James Aldridge's story, scored by Mieczysław Wejnberg, a graduate of the Miensk Conservatory, can be considered the first known example of Belarusian electronic music, as well as Belarusian blues. Wejnberg's electronic compositions performed by Varovič's quintet of electronic musical instruments accompany the film's underwater scenes.

But calling Wejnberg a Belarusian composer is somewhat of a stretch. Born in Warsaw, he fled to Miensk at the beginning of World War II, where he managed to graduate from the Conservatory, and later evacuated to Toshkent during Germany's invasion of the USSR. He would eventually end up in Moscow, where he spent the rest of his life.

The soundtrack for the film 'Dzikaje Palavańnie Karala Stacha' (King Stakh's Wild Hunt) (1979) is perhaps a better candidate for the first truly Belarusian electronic film score. The music for the film's soundtrack composed by Jaŭhien Hlebaŭ and performed by his disciple Uładzimir Kandrusievič was recorded in Melodiya’s (the sole official record label and music publisher in the Soviet Union – translator’s note) studio in Moscow.

The state-of-the-art studio featured one of thirty Synthi 100 synthesizers ever produced. This iconic piece of electronic music history was used, among others, by Karlheinz Stockhausen, Stevie Wonder, Russian electronic music pioneer Eduard Artemyev and Delia Derbyshire to score the earliest episodes of the legendary Doctor Who series. It was upon Eduard Artemyev's request that Melodiya procured the unique piece of music technology for their studio. According to Kandrusievič's recollections, he had to improvise during the recording of the soundtrack. Hlebaŭ composed a piece featuring complex chord structures, not knowing that the mighty synthesizer was actually monophonic. Besides that, Eduard Artemyev, who composed the Stalker soundtrack on it, recalls that the particular variant of Synthi 100 in Melodiya's studio did not have a digital sequencer on board, i.e. effectively no memory storage. You can check out how that score sounded in one of the final scenes of 'Dzikaje Palavańnie Karala Stacha' here.

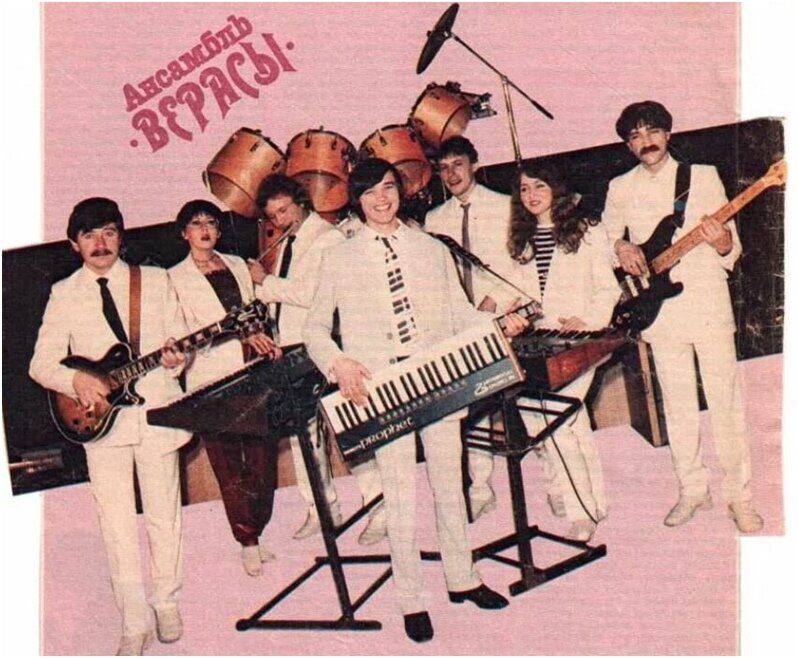

<iframe width="560" height="415" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/cofHse0S9Nw?si=HNvHRjD-UELV_TVu" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" allowfullscreen></iframe><h2>Disco Carnival</h2>Viktar Siamaška also talks about another student of Hlebaŭ's – Vasil Rainčyk, a member of VIA Vierasy. Vierasy recorded their hit 'Malinaŭka' in the very same Melodiya studio in Moscow around the same time – in the late 70s. Rainčyk recalls that the recoginzable faux-whistle sound heard at the beginning of the track was actually a happy accident on the newest Moog synthesizer in that studio. He liked the sound he stumbled upon so much, that he decided to leave it in the final version of what soon became a big hit.

This experience led to the group getting a hold of a synthesizer and a computer for their own needs, which immediately reflected in the arrangements of their tracks in the early 80s. In addition, Rainčyk wrote academic instrumental pieces for electronic instruments, including 'Nazad Da Zorak' (Back to the stars) (1985) and Žyćcio Artysta (The life of an artist) (1986). He also wrote an electronic score for the children's film 'Palot U Krainu Pačvaraŭ' (Flight to the land of monsters). The song 'Karnaval' (Carnival) by Vierasy became a hit all over the Soviet Union in 1984. It features a drum machine in tropical-disco style and a dubbed-out mid-track build-up which make for an arrangement that somehow sounds fresh today.

<iframe style="border-radius:12px" src="https://open.spotify.com/embed/track/2bYlym0aJNt9gv0PjCgypv?utm_source=generator" width="100%" height="152" frameBorder="0" allowfullscreen="" allow="autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; fullscreen; picture-in-picture" loading="lazy"></iframe><h2>House and Techno. The Virus of Freedom</h2>The development of early electronic music was heavily influenced by scarcity and accessibility – limited access to technologies that were true game-changers at the time, and primarily, of course, scarcity of knowledge and information. Both factors were especially pertinent for the countries behind the Iron Curtain.

In 1987, German DJ Westbam was invited to Riga for the "Exhibition of Approximate Art" where he presented innovative DJ mixing techniques to local DJs Janis Krauklis, Ugis Polis, and DJ Eastbam. The festival was also attended by notable artists from Leningrad: Sergey Kuryokhin with his paradoxical stage show Pop-Mechanics and members of the band Kino, including Viktor Tsoi. Westbam performed together with Soviet musicians, joining an avant-garde jam session with his innovative sampling and scratching. This is how the house virus first infiltrated the USSR.

<iframe width="560" height="415" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/videoseries?si=GPij_vCsfO6dUY7b&list=PLASCQv-bEgAgsyh56QygNdk2l2VHpnABs" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" allowfullscreen></iframe>In Leningrad, the scene was ripe for a sonic revolution: local artists actively experimented with new artforms and often lived and partied in squats. One of these places – at Fontanka 145 – became a hotspot for the spread of electronic dance music in Russia. Parties were also held at the House of Communications Workers and at the Leningrad Planetarium, and a week after the dissolution of the USSR on December 14, 1991, the first big rave called Gagarin Party rocked the Moscow VDNKh pavilions, marking the starting point for the wide spread of rave culture in the now former Soviet republics. Gagarin Party marks the first introduction of the Miensk scene to the futuristic rave concept, with first Belarusian techno party organizers-to-be Claus, Saša Lisic, Ajrat 'Alik' Chuzin all taking part in organizing the event.

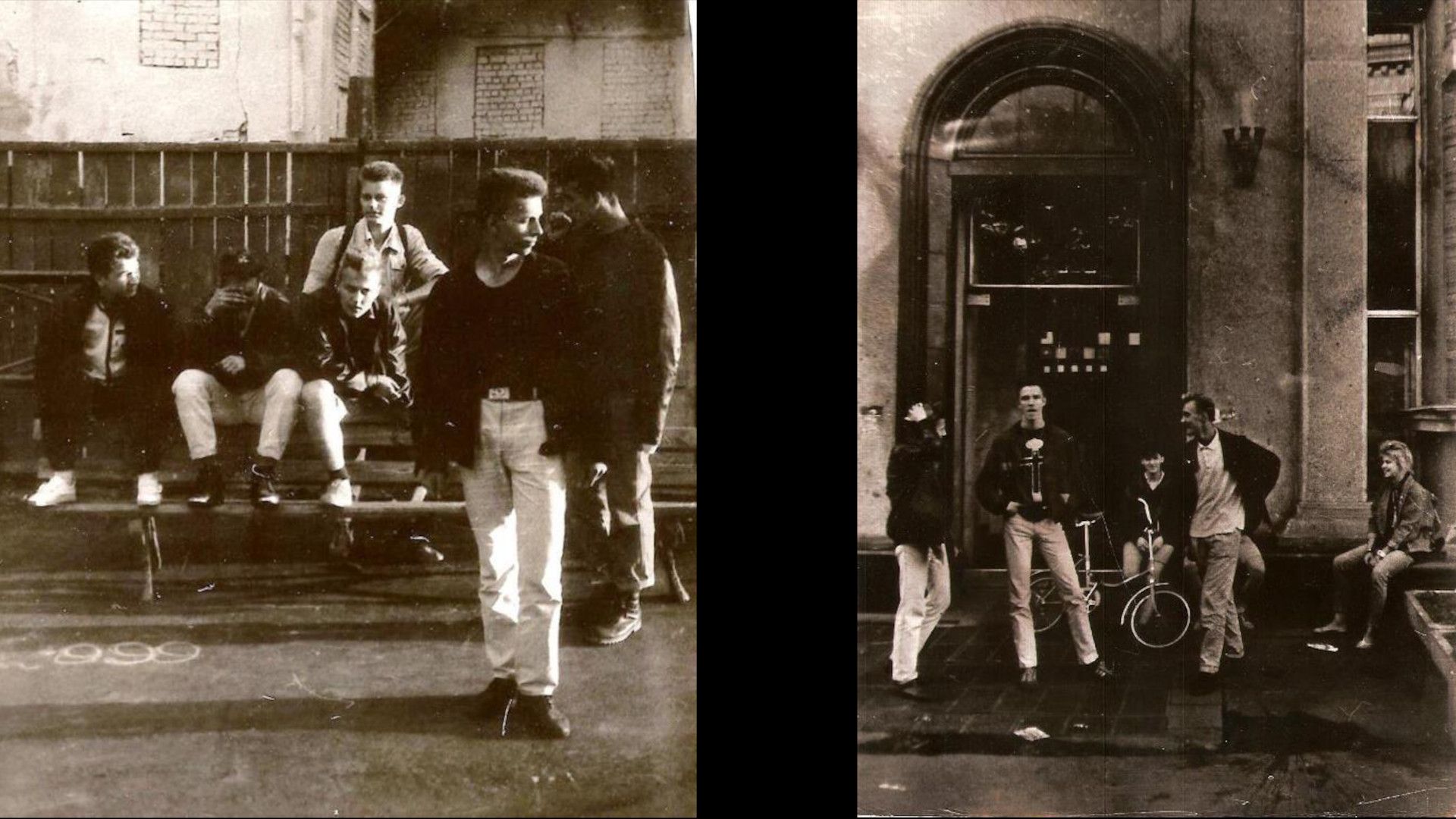

<h2>Gagarin Party: Cosmonauts and the French Ambassador</h2>"It all started in 1991 when I met my friend's boyfriend Andrej Afanaśjeŭ, a.k.a. DJ Claus," recalls Ajrat Chuzin in an interview for Relax.by. "We hung out downtown, the whole scene gathered in Panikoŭka, Troickaje Pradmieście and Pingvin cafe. We were all on a steady musical diet, although getting a hold of good music was no easy feat. You would borrow and copy cassettes from friends. You had to seek out and maintain good relationships with people who knew this music and had the tapes."

At one point, Andrej told Ajrat about his friend from Saint Petersburg Ivan Salmaksov who was into music and wanted to organize night parties in Moscow and St.Petersburg. Ivan Salmaksov was a Russian DJ and promoter, one of the organizers of Moscow's first raves Gagarin Party and Mobile. Claus had met him in Poland, where their fathers were stationed as Soviet Army officers.

"From the very first day, we hit it off somehow, finding a common interest in music. He showed me his music collection, and within a month, we were organizing school discos," recalls Andrej 'Claus' Afanaśjeŭ. After a while their families returned home: Claus's to Miensk, and Salmaksov's to Leningrad. "When I arrived in Miensk, I called Ivan, who had just returned from America with music gear – a synthesizer, keyboards, a reverb unit, and a drum machine. It was a basic electronic setup one could use to create minimalist electronic music in the style of Depeche Mode. He invited me to St. Petersburg, and we spent a week at his place, recording a 90-minute cassette.

Later, Ivan, his friend Zhenia Birman, and Lyosha Haas from Fontanka came to Moscow and got directly involved in organizing the Gagarin Party. I witnessed the entire organization process. I was directly involved in the promotional campaign, handing out flyers, meeting the guests and musicians, and arranging their hotel accommodations."

Amid the chaos of organizing the party, they completely overlooked assigning staff for the cloakroom. Andrej's friends from Miensk Saša Lisic and Ajrat Chuzin, who came to Moscow for the party on Andrej's invitation, stepped in to help. Here's how they recall that event in a LiveJournal post:

"What we saw in the 'Kosmos' pavilion had a truly astounding effect on us. The new groundbreaking music, the lights, the lasers, the massive crowd, and most importantly – the overall atmosphere. It was unforgettable. More than three thousand people came to the party. Celebrities and actual cosmonauts were spotted among the guests. Even the French ambassador came. Thousands of young, beautiful people danced non-stop among the exhibits in the pavilion. All in a friendly welcoming atmosphere. Stark contrast to what was going on in Miensk at the time. Inspired by what we saw, we were eager to organize a similar party back home."

<iframe width="560" height="415" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/35iu1Ww6Lik?si=NSrV4NpQ0XeIHjDG" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" allowfullscreen></iframe><h2>20-Minute Techno Chunks in Houses of Сulture</h2>By the end of the 80s underground electronic music spreads to Belarus. One of the first DJs to play the new sounds at local discos was Alexi Kutuzov, a.k.a. DJ I.F.U.

Alexi Kutuzov: I turned 14 when my sister introduced me to her friend's husband, who worked at the disco of the Railway Workers' Palace of Culture. By then I was already traveling with my mother to Poland to sell stuff at open-air markets and in there I found these music kiosks with cassettes. Sister's friend's husband came to visit us, saw my tapes and said, 'Nice collection! Can I borrow some stuff to copy? By the way, come around to our disco.' That was April 1991.

Of course, I was in. Their disco had youth nights, but also 30+ nights and senior citizen nights. Tangos and waltzes for the latter. I immediately joined the team. At first, I worked the lighting, pressing keys to turn colored lights and the disco ball on and off.

My first time DJing was in June 1991. The resident DJ got sick and the guys asked me if I wanted to try. It was a senior citizen night. We were working the reel-to-reel tape players. I played well that night, accompanied by an MC, so they invited me to host the 30+ night, and then the youth night. As time went on, the previous resident DJ fell off so I eventually took over. We did not stay long at the Railway Workers’ Palace of Culture. Over disagreements with the management we left it to find new home in ‘Junactva’ Vocational Education House of Culture on Maskoŭskaja Street. I played there until fall of 1993, becoming DJing partners with the sister's friend's husband.

We opened up a bar there. We would buy 20 cases of beer in the neighboring grocery store and sell it at the disco at twice the price. We called the place Music Cafe Red Hall. We had a bar and a dance floor for 150 people upstairs with a sizable lobby downstairs. We had all the equipment: the soundsystem, the reel-to-reels, the mixing console. The House of Culture was in charge of disco nights for the trade schools and technical schools, also playing general admission discos for the district. We would have ‘bratva’ (Russian slang term for gang members and affiliates – translator’s note) from Kurasoŭščyna (a residential area in the southwestern part of Miensk – editor's note) in attendance, as we were located close to the city center, Maskoŭskaya Street, right behind the consumer services center.

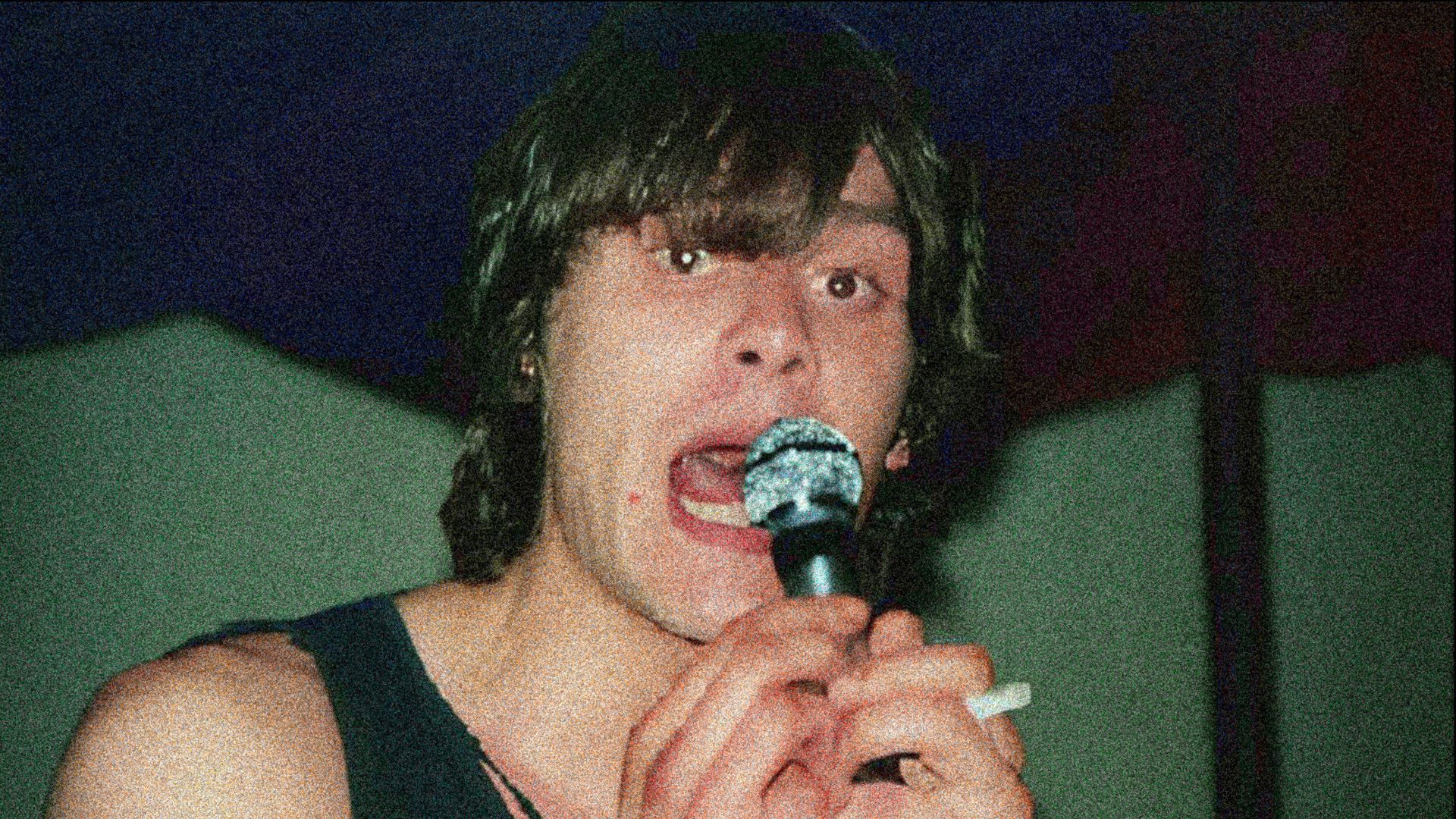

Eventually I would become the sole resident DJ there. I had a strict rule: no Russian or Soviet music, no pop hits. Only foreign dance tracks and slow dance songs. I started inserting underground electronic tracks, doing it in chunks so as not to annoy the audience, who were more used to Dr. Alban, Ace of Base or Haddaway. Literally playing 20 minute chunks of some Dutch techno, first tracks by the Prodigy, and later Orbital and A Guy Called Gerald. The stuff I would buy in Poland or exchange at the record collectors' club.

Soon the word spread around about our disco on Maskoŭskaja Street. People started coming from all over town; from Zakhad (a residential area in Miensk – editor's note) came a big crew I knew from the Dynama stadium. They would bring down their own ‘bratva’. The downtown crew also made their appearances. I stuck around for another six months and then made a dramatic exit when the Kurasoŭščyna crew got bored one night and beat up my Zakhad friends.

It was about that time, when a friend told me about this new party with no hits, no slow dances and no breaks. And no MC on the microphone. 'You gotta meet those guys!' he said.

That party was organized by the crew that witnessed the Gagarin Party in Moscow first-hand a year prior.

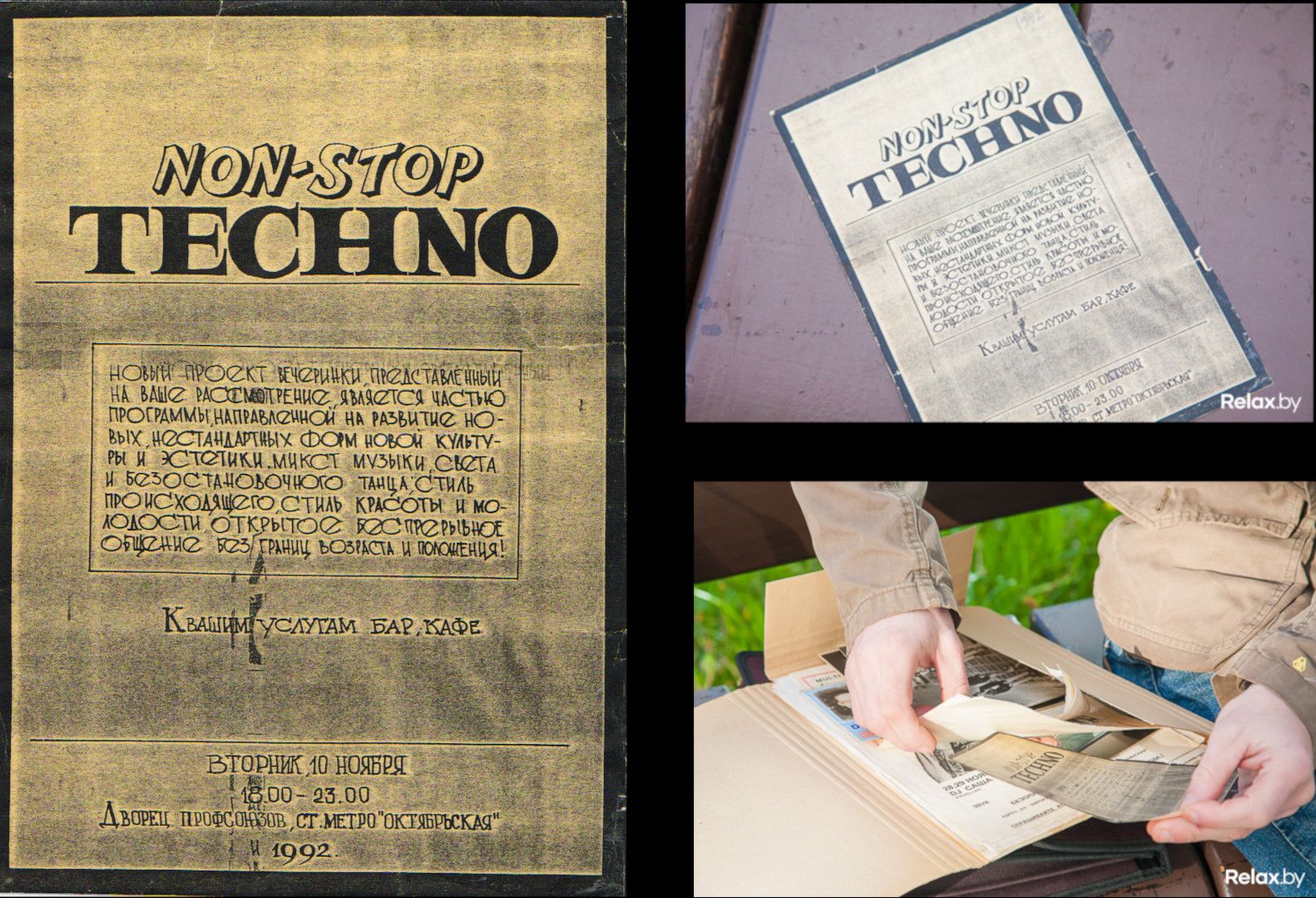

<h2>‘While the City Ignorantly Slept’</h2>Upon returning to Miensk from the Gagarin Party, the crew began preparations to what was to finally unfold in the fall of 1992. The Palace of Trade Unions was chosen as the venue for the first all-night Non-Stop Techno Party. The Palace already held discos on Saturdays and was located close to the favorite hangout spots of the local hip youths. They hand-drew flyers outlining the event concept, made a stack of photocopies, and then took to the streets distributing invitations to the free party to everyone they liked.

Due to organizational issues, the party was once rescheduled, and finally took place on November 10, 1992. The soundtrack of the party consisted of pre-recorded mixes the guys brought back from Moscow and St. Petersburg, alongside select recordings from Saša Lisic's decent CD collection he brought over from Germany. A lot of people showed up and generally enjoyed the event, but as the organizers admit, the crowd was not the target audience they had hoped for.

Alik: For us, it was a failed attempt at organizing a techno party. First of all, it was an evening event, just like every other disco in town. And secondly, the free party attracted a very random crowd including everyone but the people we counted on.

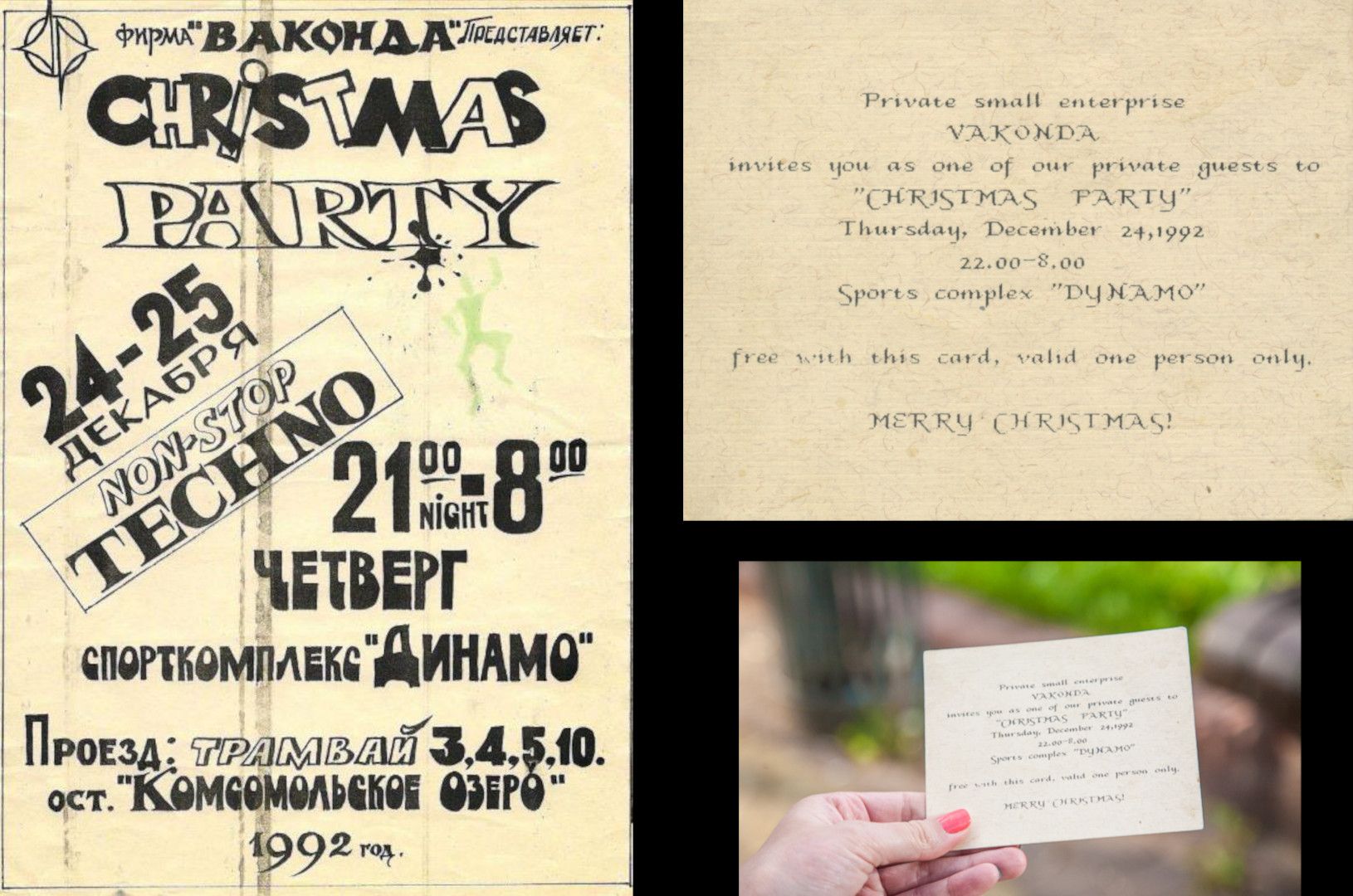

After the first ‘test’ party attracted a large crowd, the crew decided to go all in and organize a full-scale night-time rave. Following the formula successfully employed in Moscow and St. Petersburg, they chose the largest venue available at the time – Dynama sports complex on Daŭmana Street – a place that, by the way, still looks the same, except the addition of a velodrome.

The organizers went to great lengths to procure the sound system big enough for a venue of that size. The only organization in the city that had sufficient equipment at that time was the State Orchestra under the direction of Mikhail Finberg. All that was left was to find the funding for this grand plan.

Soon, Maniešyn and Chuzin met their friend Alaksandr Ciarlecki, known in the scene as Saša Krolik. He was DJing at one of the trendiest discos in town – the one in the building 8 of BPI (Belarusian Polytechnic Institute – translator’s note). Saša Krolik quickly came on board because he understood the concept completely, having visited St. Petersburg's Fontanka squat parties himself. By chance, they ran into Saša Krolik’s university friend Ihar Šuplecoŭ. Ihar was intrigued by the idea of holding a rave at the large sports arena and agreed to finance the event.

The party was scheduled for the night of December 24-25, 1992, and was dubbed The Christmas Party. Promotional flyers and posters designed by Saša Maniešyn were distributed throughout the city. There were even TV and radio ads for the revolutionary new type of disco.

Alik: We were full of ambition and high expectations, so we told everyone that the party is going to attract a huge crowd and we’ll make a ton of cash. We promised everyone the stars and genuinely believed it ourselves.

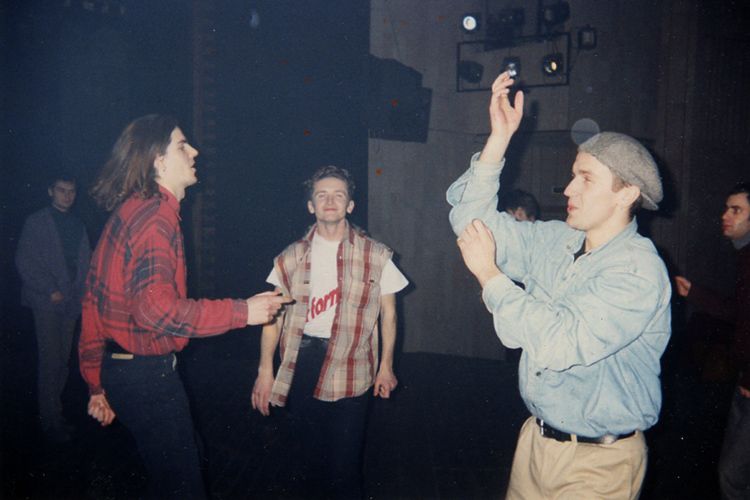

However, the event was so unconventional and out of place for Miensk of the day, that, contrary to our protagonists’ expectations, no more than a hundred people showed up, most of whom were their friends and hipsters from ‘truba’ – the underpass at Kupalaŭskaja metro station, a popular downtown hangout spot. When the huge speakers were delivered and set up in the arena, it became clear that they were way too powerful for the space. As a result, they used only about six kilowatts of the total power. And even still, it was so loud that barriers were put up 3-4 meters away from the speakers to keep people for coming too close to the soundsystem.

Valodzia, one of the attendees of the historic first rave recalls: There were maybe 10-15 people on the dancefloor itself. The rest were milling about in the hallway hesitant to enter. Many did not understand what was happening at all: instead of Pugacheva and Leontiev (Soviet/Russian pop stars of the era - translator's note) – weird loud music playing, lights flashing, lasers everywhere, some transsexuals in tight dayglo oufits – a wild gathering of party animals. Some unprepared guests, unfamiliar with this kind of music had genuine psychedelic episodes. The atmosphere itself was enough to induce altered states – panicked people were seen scrambling around the arena unable to find exits. The image seems wild nowadays, but that's exactly how things started.

Saša 'Krolik' Ciarlecki: I knew a guy who worked as a journalist for the newspaper Znamya Yunosti. He always listened to our stories eagerly and really pleaded to invite him to this big upcoming party we kept bringing up. Finally, when the rave happened, he came, and a few days later, the newspaper published a double-page spread article titled 'While the City Ignorantly Slept' describing the party as a satanic orgy where bewildered youths lost their minds roaming an arena.

Everybody except the organizers and the sponsors made their money from the first rave in Belarus. But this didn’t discourage our heroes at all. What mattered to them was the emancipation that rave culture embodied – a capsule of freedom that brought the spirit of equality and expression from New York and Chicago clubs across the ocean. This sense of emancipation was especially significant in the post-Soviet reality, where on the one hand lay the entire Soviet experience, and on the other was just this: powerful sound, relentless rhythms of new music, and young, beautiful people dancing. This in itself was amazing enough.

Less than a week later the crew played another party at the building 8 of BPI (currently BNTU) and began preparations for the next full-scale rave. Word of mouth gradually took over: rumors spread around the city about a mysterious crew organizing new-format nighttime parties. It was the time when a brand new cultural elite began to emerge – artists, film and theater directors, musicians, and the emerging class of partygoers who had already attended this type of parties in Western Europe or the Russian capitals and knew what to expect. The parties moved to Miensk’s theaters, arts palaces, and cinemas. Early 90s saw the renaissance of Belarusian culture, and underground dance parties were part and parcel of this revival. More on that in the next installment of “Ikarus: Stories of Electronic Music in Belarus”.

Check out the podcast on Spotify, SoundCloud and Apple Podcasts

Translation into English by Alik Khomiak, artwork by Yana Zenovitch