The Media and Labels: From a Music Newspaper to TV and Radio

What were the music media reporting on electronic music in 90s Belarus?

The previous extended chapter of our story focused on Belarusian musicians and their music. Today, we will highlight another important component of the scene – the media. Where did Miensk electronic musicians get to know each other and learned about new releases? How did Muzykal'naya Gazeta and FM radio shows become hubs for the scene's growth? What did it mean to create an electronic music label in the 1990s? Let's dive in and find out! Belarusian-language text version is available on 34mag.net.

If you speak Belarusian and Russian, we highly recommend checking out the audio version of the story for full immersion. All you need to do is press play, close your eyes, and take a ride the old Ikarus bus through Miensk’s iconic nightclubbing spots of the era.

<iframe width="100%" height="450" scrolling="no" frameborder="no" allow="autoplay" src="https://w.soundcloud.com/player/?url=https%3A//api.soundcloud.com/playlists/1859530263&color=%23ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&show_teaser=true"></iframe><div style="font-size: 10px; color: #cccccc;line-break: anywhere;word-break: normal;overflow: hidden;white-space: nowrap;text-overflow: ellipsis; font-family: Interstate,Lucida Grande,Lucida Sans Unicode,Lucida Sans,Garuda,Verdana,Tahoma,sans-serif;font-weight: 100;"><a href="https://soundcloud.com/radioplato" title="Radio Plato" target="_blank" style="color: #cccccc; text-decoration: none;">Radio Plato</a> · <a href="https://soundcloud.com/radioplato/sets/ikarus-all-episodes" title="Ікарус: гісторыі электроннай музыкі Беларусі" target="_blank" style="color: #cccccc; text-decoration: none;">Ікарус: гісторыі электроннай музыкі Беларусі</a></div><h2>Vinyl Collectors Club</h2>We start our journey at the Vinyl Collectors Club, which gathers every Saturday, probably even to this day, at the Tractor Factory House of Culture to exchange or sell vinyl records, discuss music, and simply meet fellow music enthusiasts in person. According to Micia Hryšanaŭ (DJ Mitya) the Club exists since about 1985. There is very little info about it online, so we decided to ask our protagonists to find out more about it.

– I didn't just visit the Vinyl Collectors Club, I was practically a regular there, – Mitya shares. – It was part of my Saturday routine: you go there and see these older guys carrying crates of records. Very few younger people, mostly 35+. I’m a seasoned vinyl enthusiast, so I was always looking for some rare full-length albums and singles. Occasionally you would stumble upon things there that you would never find online. Of course, there is always Discogs, but it feels better to buy from this old guy. Once I saw the guy selling the yellow Kraftwerk album – ‘Computer World’. That's a record I've never seen original pressings of before in real life. 'How much?' 'Twenty dollars.' And it's a first pressing in near mint condition. That's the type of finds you go there for.

<iframe style="border-radius:12px" src="https://open.spotify.com/embed/album/42hCHiMtfs7mfBTVX3V6k7?utm_source=generator" width="100%" height="352" frameBorder="0" allowfullscreen="" allow="autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; fullscreen; picture-in-picture" loading="lazy"></iframe>According to Alexi Kutuzov, a whole array of Belarusian indie bands, including electronic musicians, emerged from the vinyl and CD collections at the Vinyl Collectors Club. For instance, that's where he met Vadim Militsin from Autism. It was also where he got Coil's Snow EP which helped him link up with DJ Claus. Here's what Vadim recalls:

– Back in the day this whole culture centered around listening to the same music. I used to meet friends and exchange records near a metro station every day after work. There was a constant exchange of music. It was quite a wide circle of people, so whenever I got some new albums, it took time for them to make their way back to me. The same was true for everybody.

By the way, the club still exists to this day. Every Saturday at noon, vinyl enthusiasts of Miensk gather on the first or third floor of the Tractor Factory House of Culture.

The independence of Belarus provided a significant impetus for the growth of Belarusian media, which actively began to take an interest in its own culture, including Belarusian music. Niamiha newspaper, first published in 1994, was one of the first local publications dedicated entirely to music news. The newspaper covered news about rock, rap, and metal, occasionally touching on electronic music as well, including local artists, like the interview with DJ Сlaus about the Dutch DJs visiting Alternatyŭny Teatr. It also published global charts and readers' personal ads, which today read like a very touching capsule of time:

- Fans of the best singer of the world Michael Jackson! Let's become pen pals! Waiting for your letters! G.

Or:

- Greetings to all fans of haunted houses and godforsaken robbed graves! We are here and waiting for you! Doom Metal fan club would like to wholeheartedly thank bands Hospice and God's Tower for providing their demo tapes and info. Our fan club is waiting for you. Amin. G. Horki, Tel'mana Street, Alex Wihrow.

Niamiha newspaper was published in an 8-page A3 format, with a print run of up to 20,000 copies. About 100 issues were printed during the publication's run, which ended around early 2000's. A vk.com group Vystavka-muzej 'Russkoje Podpolje. Oskolki' has archived about a half of the publication’s issues.

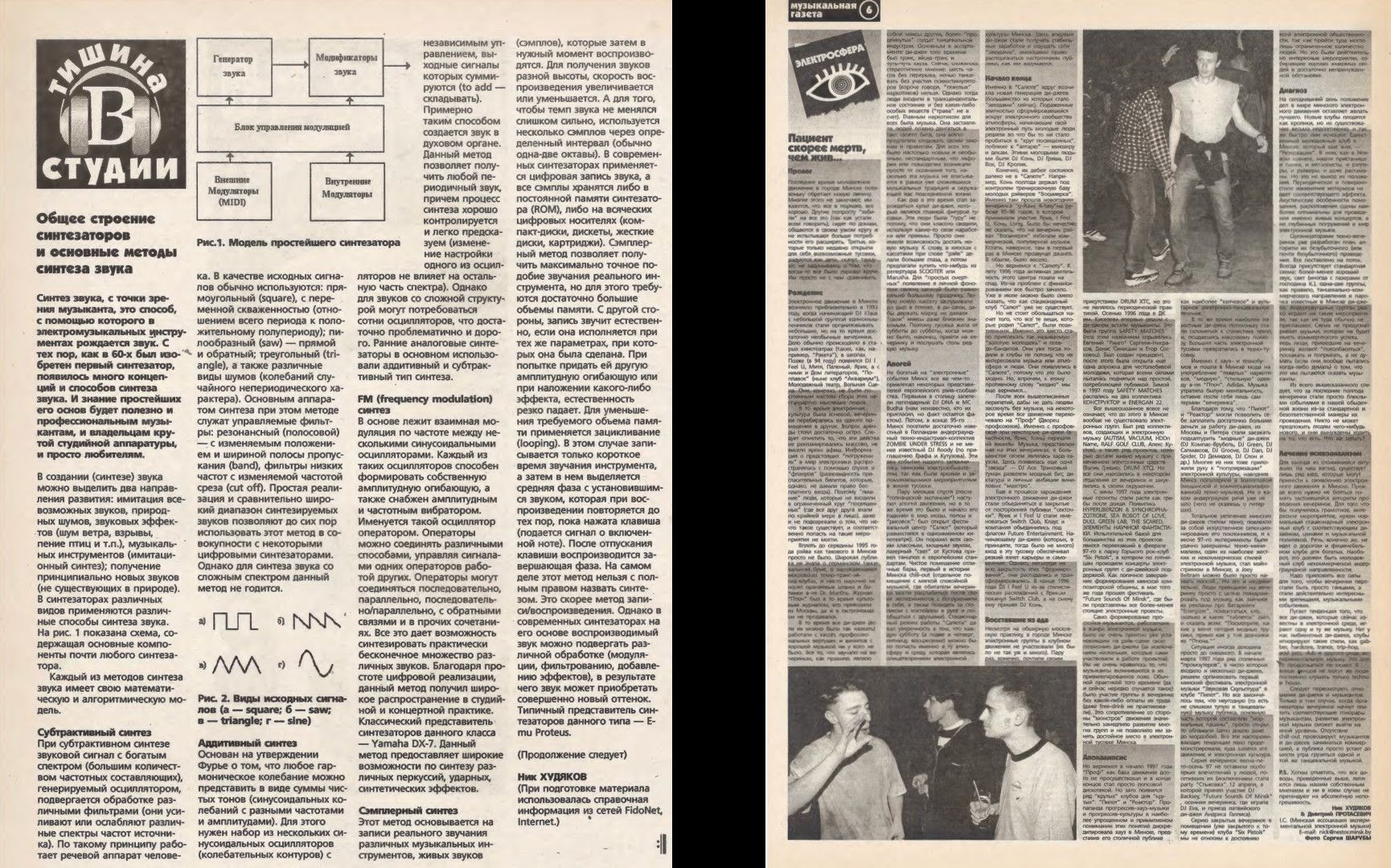

Muzykal'naya Gazeta (Music Newspaper) was a real media gamechanger in the newly-independent country. The paper started in 1996 and played a crucial role in spreading information and facilitating communication among those involved in the scene. For a good few years it became perhaps the most important publication for various music scenes, ranging from rock and folk to all kinds of electronica: from experimental to rave, to dark industrial scenes. Muzykalka (as its name has been affectionately abbreviated by devoted readers) featured regular columns dedicated to electronic music, reviews of new foreign and Belarusian releases, interviews with Belarusian artists, DJs, and promoters, as well as educational articles about genres, techniques, and the craft of DJing. The newpaper's authors included electronic musicians: Mikita Chudziakoŭ, Dzmitry Pratasievič, with industrial scene represented by DJ Commando Labella. Besides the articles the newspaper also featured the personal ads, that music fans used to exchange information, music, contacts, and met one another. We had an in-depth conversation about Muzykal'naya Gazeta with Mikita Chudziakoŭ, who, along with Dzmitry Pratasievič and Alaksiej Kustaŭ, ran the column Electrosfera from 1997 to 2001, which was entirely dedicated to electronic music.

– When I saw the first issues of Muzykal'naya Gazeta, I, like everyone else, was very impressed to discover that there was such a high-quality music publication in Belarus. It's worth noting that it was the time, when music was very important for the youth; it was one of the primary ways to express who you are and how you define yourself. And the press was pretty much the only source of new information about music. For instance, we had no idea how electronic music was actually made. You would hear the phrase 'analogue synthesis' in some interview and start digging from there.

Muzykal'naya Gazeta was a great centralized source for such tidbits that you could use in your research. So, it’s no surprise that it immediately caught my interest – I would rush to buy the newspaper in the kiosk every week. That's how I first thought of working there. It seemed like a real dream job at the time. I had no experience in journalism, so I wrote three articles about MIDI devices to demonstrate that I could do it. They liked the articles and published them over several issues.

So I went ahead and suggested starting a regular column about studio equipment. That was a first. I also secretly hoped that writing such column I would have the opportunity to visit music stores, try out all sorts of equipment, talk to specialists, and then share that information with readers. The column was called ‘Cišynia ŭ studyi’ (Silence in the studio). When the editors found out that I was also a fan of electronic music, they started offering me to write articles about it and reviews of electronic artists.

Along with Mikita his friend and band-mate from Elementy Nauchnoi Fantastiki Dzmitry Pratasievič also wrote for the paper. The two were then joined by Alaksiej Kustaŭ, who had recently moved from Navapolacak to Miensk and was actively becoming involved in the capital's cultural scene.

– It was Mikita and Dzima's idea, – says Alaksiej. – We did often work together: I would translate a part of an article, Mikita handled another part, and Dzima took care of yet another part. Many people came through our office. I wasn't writing exclusively about electronic music – I also had contacts with all sorts of musicians and wrote opinion pieces. The pay was modest, just enough to cover new strings for my bass guitar. It was primarily a lively and dynamic place, with lots of rock and jazz musicians coming through. They would bring their latest albums, discuss their recent live shows. A lot of materials were also constantly being received by mail. All in a day's work of an editorial office. Great times!

– We became part of an amazing team, – Mikita adds. – For some time, I felt like a character in Strugatsky brothers' novel, ‘Monday Begins on Saturday’. Which was completely at odds with my preconceived ideas of a grown-up office job. A creative team, a creative approach to everything, come whenever you want, as long as the work gets done. Dzmitry Bezkaravajny was the editor-in-chief, Aleh Klimaŭ was in charge of the newspaper in general and particularly of the ex-USSR music market coverage. Another notable journalist working for the newspaper was Iryna Šumskaja, who wrote about experimental music.

Perhaps, the most exciting thing was that our office had an internet connection. That was extraordinary and groundbreaking for Belarus circa 1996 – to be able to go to The Future Sound of London official website and read their latest interview. We would take turns using the internet, logging our 15 or 30 minute sessions in a register. The internet connection was through a dial-up modem, with a special phone number you dial to connect. Terribly slow. When researching you would open 15 tabs and go for a smoke break. By the time you returned they had hopefully loaded. The good old days.

After starting the studio equipment column, Mikita had the idea to start the column dedicated to electronic music. The newspaper was covering pop, rock and metal and Mikita felt like his favorite genre should have representation too:

– It has to be noted, that back in the day very few people took electronic music seriously in Belarus. It was simply not real music to most people if it had no drummer and guitar player. I really wanted to change that perception, as the abstract electronic music felt like the future of music to me. Guitar is great, but its heyday has passed, experimental effects are where it's at.

Eventually, the newspaper's publisher Anatol' Kiruškin agreed on condition that all ravers of the country would read it and write in.

– So we had to do our best, – says Mikita. – We called the column Elektrosfera. It had two parts: global and Belarusian. Foreign artists are all well and good, but we also wanted to support whatever was happening locally. I never denied anyone who wanted to promote their party or new album. That was our goal. Our only condition was that we had to hear the music first.

The correspondence that Muzykal'naya Gazeta received from it readers is worth a separate mention. Especially for electronic music fans.

– Lots of music fans wrote in because they felt lonely in their small towns, where they were the only person with dyed hair who listened to techno, while everybody around them listened to Sektor Gaza (a controversial Russian pop-punk-meets-folk band popular with gopniks – translator’s note). All these letters really warmed our hearts and we were delighted to answer them. We tried to answer everybody, along the way creating a community of like-minded people. That felt really important to us.

The newspaper flew off the newsstands’ shelves, you could also subscribe to get it delivered to your mailbox. Besides Belarus, it also circulated in Russia, Ukraine and even Moldova. Interestingly, despite its popularity, Muzykal'naya Gazeta was not a profitable business, due to the peculiarities of local regulations, a limited musical market etc. The newspaper was part of Nestor publishing house, who also put out Kompjuternaya Gazeta (Computer Newspaper) about the IT news, Virtualnye Radosti (Virtual joys) about videogame news and Setevye Resheniya (Network solutions) magazine. Profits from these publications were used to cover Muzykal'naya Gazeta's operating costs. The newspaper was in circulation until 2008, when computers were becoming permanent fixtures in readers' homes. An online digital archive of Muzykal'naya Gazeta is maintained by the Nestor publishing house, so you can easily trace back the history of Belarusian and foreign music through its issues.

<h2>Labels: Delta 9 Records</h2>Labels are another important ingredient of Miensk electronic scene of the 90s. The needs of local music listeners at the time were served by so-called 'record companies', that were essentially pirate cassette manufacturers. The practice that, of course, did not support the artists, but at least spread their music to the local audience. Electronic music was sometimes released by these pirates as well, in addition to more popular pop, rock and metal albums.

The first real electronic label in Belarus was Delta 9 Records, created in 1996 by Vadim Militsin of Autism. We mentioned the label in previous chapters briefly. Time to cover it in more detail. The label's history begins with Vadim dubbing cassette copies of his own releases as Autism and On The Edge to hand out to friends.

– I did these cassette micro-runs, until computer CD-ROM drives with recording functionality appeared. It was, of course, a culture shock: you could now record your own CDs at home. They were rather pricey, plus it was right after the financial crisis of 1998, when Belarusian ruble lost its value several times over. But, again, my parents helped me out by giving me 200 dollars to buy a CD-ROM drive. It took a long time to burn a CD-R and every once in a while you'd get an error, but it was mind-blowing anyway.

In 1997 the label released its first compilation titled Zapakh Elektrichestva (The smell of electricity) with the help of Aliaksandr Dubinin from a commercial studio BMM.

– He sold CDs and cassettes in two shop in the city, and he decided to carry our releases as well. I would come by once a fortnight to check how they were selling and he would give me the money. That’s how it worked.

Soon enough the label gathered most of Belarusian abstract electronic projects of the day, including such acts as Autism, Vacuumable, Dulgreen Lab, Alex Coostoff, Energun 22, Chameleon, Spastic Fingers and others.

– Almost all notable electronic musicians from Belarus were released through us. Plus we started putting out DJs' mixtapes later on as well. It all began taking on some sort of scale. But it was still pretty small and cozy. We all knew each other, met at parties and festivals. We would check out new artists there and offer them releasing an album.

Musicians made no money on it, by the way. I was constantly in the red because of frequent CD-R recording errors, which rendered them useless. But we had the desire to spread the music so that people would hear it and come to party or buy the next release.

By 2000 the label had released about a dozen different artists. During its run the label has put out almost thirty releases. Nevertheless, the press runs remained minimal: CDs were released by the dozens, while cassette runs maxed out at a couple of hundred copies. The label essentially ceased operating when Vadim emigrated to the US in the early 2000s.

<h2>Labels: I&I Group Records</h2>In the late 1990s, another significant label emerged that focused on electronic music: I&I Group Records. While Delta 9 primarily released albums by Belarusian artists, I&I focused on local DJs – both labels presenting cream of the crop to the listeners. I&I Group Records roster included such DJ names as Сlaus, I.F.U., Yarik, Kon', Mitya, Box, Lioša Patapiejka and others.

Micia Hryšanaŭ recalls: The label was created by two of my good friends Dzima 'Mr Bars' Kuzmin and Paša 'Termik' Pietryščaŭ. Besides releasing Belarusian DJs' mixes, they also put out classic electronic albums by the likes of Future Sound of London or Autechre as part of what they considered musical education for the masses. Where would you buy an Autechre album back in those days? You could find Ace of Base no problem. Their cassettes were high-quality too, people still remember them and beat themselves up for losing them in the shuffle.

You can listen to some of the DJ mixes released on I&I Group Records cassettes on magentalove Mixcloud.

<iframe width="100%" height="120" src="https://player-widget.mixcloud.com/widget/iframe/?hide_cover=1&feed=%2Fmagentalove%2Fdj-yarick-the-heat-ab-side%2F" frameborder="0" ></iframe>I&I Group Records always made a quality product. Cassettes had fold-out insert cards designed after the original packaging of the respective releases. I&I Group Records cassettes were carried by several music stores in the city and cost 2-3 times more than regular pirated cassettes.

All of label's releases would eventually make it to air on Radio Styl' (Style Radio). The label collaborated with the station closely, and the winners of the contests organized by show hosts Time Koromisslove and Alaksiej Kvakin received these very cassettes as prizes. While we’re at it, let's check out other local FM radio shows that played Belarusian electronic music.

<h2>The Radio</h2>In 1993, Radio BA begins operating as the first private FM radio station in the country. Presenters Barys Štern and Tamara Lisickaja regularly play electronic music and talk with figures from the Belarusian electronic scene on its airwaves.

One of the first shows dedicated to electronic music was called Dyjapazon hosted by Aleh Tyškievič. There is no information about it online, but musician Vitali Harmaš, known for the projects i/dex and harmash, shared an interesting story about the show. In the mid-90s he lived in Navapolacak and was already making recordings of his electronic experiments. Finally, the time had come to share them with the world:

– Somebody told me about this ‘Dyjapazon’ radio show. I recorded a cassette of my tracks and went to Miensk. Just roaming the streets asking passers-by if they knew this radio station. A few hours later somebody tipped me off that the host of the radio show in question worked at this student club near Riga supermarket. I went there and gave him my cassette. A few days later he called me and invited to the station to record a radio show.

Another electronic music show, focusing on industrial electronics, was hosted by DJ Commando Labella on Radio Mir. Vladislav Buben hosted the program called Zateriannyj Mir (The Lost World) on the same radio station about metal, rock, and experimental, including extreme genres of electronic music. In 1998, Radio Stalica aired Ultrasfera – a program about Belarusian electronic music, hosted by Siarhej Maksimčuk, a member of Energun. 1998 was also the year Radio Styl' started airing, becoming a platform for numerous author-driven programs about music – including electronic music – for the next five years. Time Koromisslove's and Alaksiej Kvakin's shows became very popular among fans of electronic music. They were regularly attended by local musicians and DJs, who gave interviews and played live on air. Some would call this a watershed period: DJs and musicians were gradually coming out of the shadows of the underground.

– At some point we started doing radio shows frequently; mostly Koromisslove's show on Radio Styl', – recalls Mitya. – Together with Yarik, with Kon'. We would do interviews and bring CDs with our mixes. Sometimes you could just hear your own set playing on FM radio while driving. Koromisslove was known for his philosophical musings in between tracks. He was quite a romantic character on the air.

<iframe width="560" height="415" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/62qr-y2uZ6A?si=8sFt4gOz79Y92wKT" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" allowfullscreen></iframe>And, last but not the least, electronic music was even played on your radiotochka (a radio transmitter connected to a government-mandated wired public address network that in peaceful times would broadcast regular radio programming instead of emergency messages – translator's note). The show was called Vientyliatar and aired weekly. DJs and musicians could go record a mixtape to a reel-to-reel tape during the day and it would be aired in the evening accompanied by an interview with the host.

According to Alexi Kutuzov, TV was barely interested in club culture or anything related to it. In the early 90s, together with Paval Karenieŭski he made three episodes of Pop-Pilot – a program about the parties in the Alternatyŭny Teatr. Three episodes have been produced and aired. Club-oriented TV programming would become more of a thing in the following decade.

<br>* * *

By the end of the 1990s, the internet was rapidly gaining popularity in Belarus. Oxidiset.net – an online forum about electronic music and clubbing – was launched in 1999. Shortly after, it spawns a promo-group of the same name organizing club nights all over town. "It was a real treasure trove of information. You could ask any question and the entire community would answer," recalled Kutuzov. Oxidiser became a massive influence on the local electronic scene around the early 2000s. But that's a whole other story.

In the next chapter, we’ll take you back to the second half of the 1990s to dive into the vibrant world of Miensk clubs and DJs. Discover how musical underdogs rose to fame on a post-Soviet scale, how Belarusians made their mark with unforgettable parties at Kazantip, and how it all suddenly faded away. All this and more in the final feature of "Ikarus: Stories of Electronic Music in Belarus".

Check out the podcast on Spotify, SoundCloud and Apple Podcasts

Translation into English by Alik Khomiak, artwork by Yana Zenovitch