From 'Salut' to Dawn: The Miensk Club Movement of the Late 1990s

Booming diversity, then hitting a downturn.

We’re wrapping up our series of articles based on the podcast “Ikarus: Stories of Electronic Music in Belarus”. In our previous installment, we explored the role of newspapers, labels, and radio shows in promoting Belarusian electronic music. Today, we’re diving back into the Miensk club movement of the late '90s. What was it really like? Where were the city’s first open-air rave held? What kind of parties did Belarusians throw at Kazantip? And how did the 1998 economic crisis impact the local electronic scene? Fasten your seatbelts — we’re taking you on a nostalgic journey through this vibrant era! Belarusian-language text version is available on 34mag.net.

If you speak Belarusian and Russian, we highly recommend checking out the audio version of the podcast for full immersion. All you need to do is press play, close your eyes, and take a ride the old Ikarus bus through Miensk’s iconic nightclubbing spots of the era.

<iframe width="100%" height="450" scrolling="no" frameborder="no" allow="autoplay" src="https://w.soundcloud.com/player/?url=https%3A//api.soundcloud.com/playlists/1859530263&color=%23ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&show_teaser=true"></iframe><div style="font-size: 10px; color: #cccccc;line-break: anywhere;word-break: normal;overflow: hidden;white-space: nowrap;text-overflow: ellipsis; font-family: Interstate,Lucida Grande,Lucida Sans Unicode,Lucida Sans,Garuda,Verdana,Tahoma,sans-serif;font-weight: 100;"><a href="https://soundcloud.com/radioplato" title="Radio Plato" target="_blank" style="color: #cccccc; text-decoration: none;">Radio Plato</a> · <a href="https://soundcloud.com/radioplato/sets/ikarus-all-episodes" title="Ікарус: гісторыі электроннай музыкі Беларусі" target="_blank" style="color: #cccccc; text-decoration: none;">Ікарус: гісторыі электроннай музыкі Беларусі</a></div><h2>Sierabranka – an Unlikely Clubbing Mecca</h2>A new chapter in Miensk's club scene began at the iconic Salut cinema in Sierabranka (a residential area in the southeastern part of Miensk – editor's note). This was a turning point when parties transitioned from spontaneous gatherings to well-organized events with top-notch sound systems, lighting, and creative art direction. It marked the rise of a new wave of DJs and promoters, laying the foundation for a more structured and thriving clubbing movement in the city.

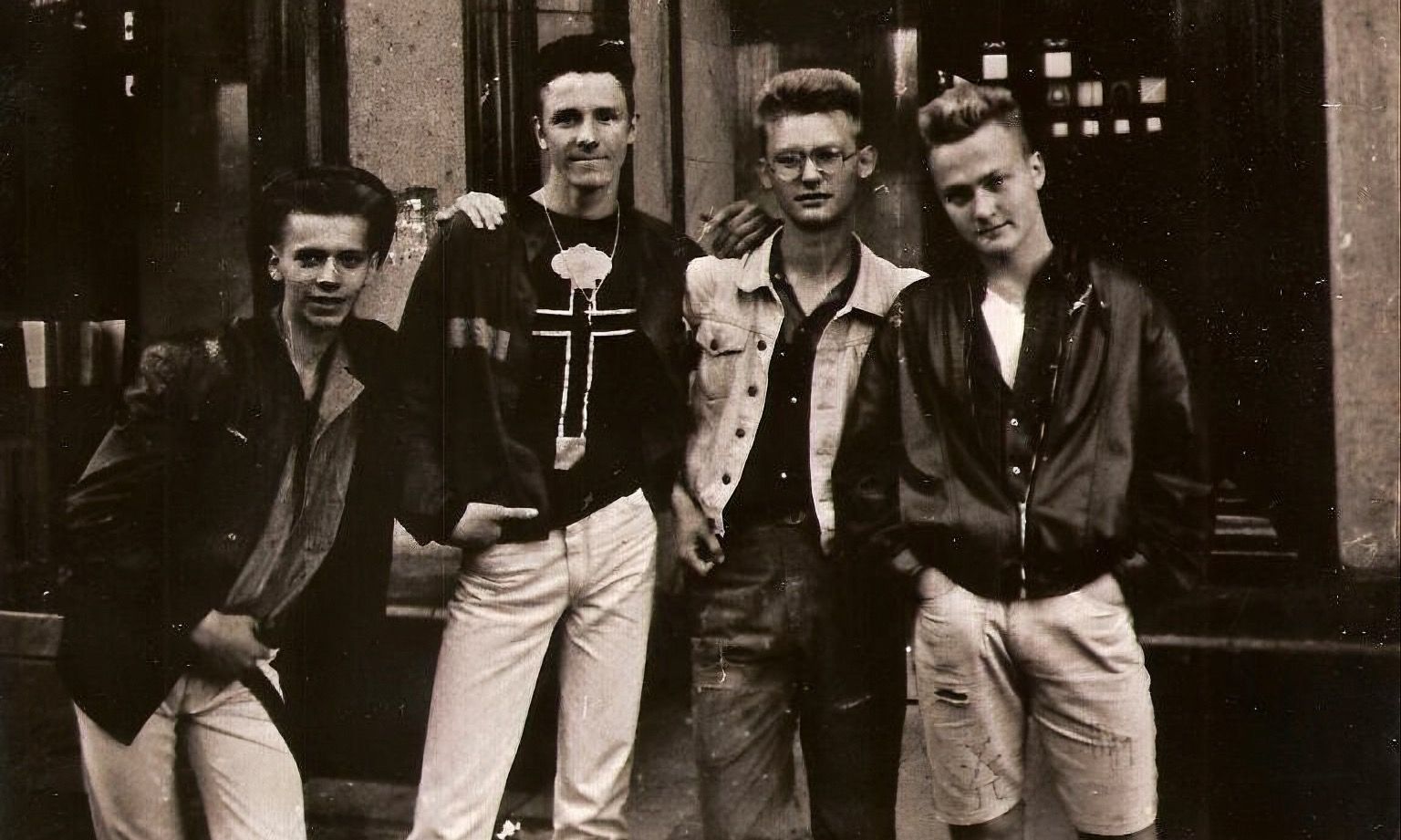

Let’s pick up where we left off: the story of Miensk’s club scene in the early ’90s wrapped up with that legendary New Year’s party at the TV studio on Makajonka in 1995. It was a pivotal moment when businessman Saša Balšavik brought in DJ Alexi Kutuzov to spin tracks for an audience of thousands, marking a significant milestone in the evolution of the city's electronic music culture. For Balšavik, the New Year's party was just a trial run, and his true masterpiece was the Salut Club, which he opened in the cinema of the same name in early 1996. Although the club existed for mere four months, it became a significant presence in the 90s electronic scene and heavily influenced its further development. How come? Let's give voice to the eyewitnesses.

– The club was open four days a week, Thursday to Sunday, – recalls Alexi 'I.F.U.' Kutuzov. – Despite not being located in the city center, on Fridays and Saturdays it would consistently gather around 600 people. The place had two dancefloors. Buses were organized to shuttle ravers directly to the club from the city center. Salut was a place that felt like home to very different kinds of visitors: from local gangsters, to businessmen, to fans of electronic music. On the main stage of this cinema-turned-club, they set up a powerful sound system, cool lights and laser installations. All this state-of-the-art equipment wowed the crowd with its capabilities weekly.

– Salut was a wonderful place, – says Micia Hryšanaŭ a.k.a. DJ Mitya. – Nothing like it existed in Miensk before or after it. To have club nights most days of the week – like in London or Berlin – was mind-blowing. You could buy a membership and attend regularly, like a gym. You would see the club advertised on the subway. The DJs that played there were becoming basically rocknstars. – Most of Miensk DJs played in Salut during its short but memorable existence: Claus, I.F.U., Mitya, Yarik, Kon', Paliony. – I still remember becoming resident there. I came to Balšavik and said that I got great music. His response was 'No need to blow your own horn, let's see you in action. I'll give you this Saturday. Let's see how it goes'. So I came that Saturday, played the entire night and everyone was simply blown away. Next words he said to me were 'Welcome aboard!'

A separate mention belongs to one of the outstanding lighting engineers of the capital who worked at the club by the name of Uładzimir Kustaŭ, namesake of Alaksiej Kustaŭ – an electronic musician from Navapolacak.

– I don't know where we would be without Kustaŭ, – says Mitya. – We'd have discos with christmas lights and candles, probably. Nobody had proper nightclub lighting back then. Only Kustaŭ did. He experimented a lot and made his own equipment. Like a d.i.y. contraption where he would pour some powder onto a hotplate to create fog.

– I must have been around 15 when I first got into Salut, – recalls Mikita Hudziakoŭ. – It made a huge impression on me because for the first time I saw that a disco could be peaceful without any fights. A huge dark converted cinema with seats removed, with a laser show and playing some great trance music. I think Salut would have been a hit even if it re-opened today. There was also a chill-out room upstairs, which I loved, because that meant that the club was not focused solely on dancing ’till you drop', but rather on musical diversity.

Besides club nights, Salut also held live shows. Drum Ecstasy and Autism played there regularly, Belarusian Climate staged their performances. There were also concerts of foreign bands, like Tequilajazzz, Naive and Agata Kristi from Russia.

Alas, the days of the glorious early Miensk nightclub were numbered. After four months of existence the club bankrupted and closed down, as did Saša Balšavik's main business. After Salut, he moved to Moscow and then returned to Miensk years later, but Salut remained his only venture into the nightlife business. In Alexi Kutuzov's opinion, "Salut did a lot of good and some harm to the local scene. It totally commercialized the whole underground movement, on the one hand, opening it up to mass awareness of the general public, and on the other – kickstarting the era of not always healthy competition. Promoters and DJs started forming cliques spurred by a thirst for money and fame, along with envy". Sadly, this tradition plagues the Miensk club scene to this day.

<h2>The Future Sound of Minsk – the First Electronic Music Festival</h2>At that time Yarik and Kutuzov had a promo group called The Switch Club. They organized a very successful party at the Aŭrora cinema, attended by about 800 people. The unexpected turnout spawned real chaos at the gate. The cashiers were hardly keeping up with the huge line of people trying to get in, as did the outnumbered security. Yarik and Kutuzov made a boatload of money, paid up their debts from previous events and then decided to part ways.

– I wanted to go in a different direction inspired by the breakbeat and drum'n'bass grooves that the Dutch DJs introduced us to, – explains Kutuzov, – while Yarik realized at this party he wanted to pursue the techno sound. He was joined by Aleksei Kon' who was also into techno back then, and I remained alone with my broken beat aspirations. Not completely alone, though – I had already started Vacuumable together with Graf and was friendly with a number of live electronic projects.

Alexi Kutuzov and Graf then formed a short-lived side-project Vacuum-Center that would organize the first festival of Belarusian electronic music The Future Sounds Of Minsk. It took place in the summer of 1997 at the very same Salut cinema, now owned by businessman Ihar Šostak.

– Šostak had a firm that rented out sound equipment for events, – Kutuzov recounts. – He moved his entire office from the city center to the second floor of the cinema, set up a showroom of sorts there, and started organizing regular pop discos for the locals. So we went to him and said 'Let's do an electronic music festival'. We brought together all the local musicians who were playing pure electronic music without vocals. A total of fifteen projects and bands. The main dancefloor was taken over by more dance-oriented acts like Vacuumable, Energun, Dzianis Pamorcaŭ's Bart the Robot and Aleksei Kon's Kanstruktar. The upstairs was all about chill-out, electronics and IDM projects such as Chudziakoŭ's Elements Of Sci-Fi, Dulgreen and -ED, Vadim Militsin with Autism and Guarana Electric projects, the latter featuring a vocalist from the band Hasta La Fillsta. Also on the line-up were Drum Ecstasy, Alex Coostoff, Valik Grishko, HDDNname, DJs Yarik and Kon'. We even had musical guests from Moscow. The project called Ministerstvo Psihodeliki brought over their analogue gear to play a live set at the festival.

After that festival it became clear that electronic live scene in Miensk does exist and is gaining momentum. Actually, in the years that followed, the number active Belarusian electronic live acts rarely exceeded that displayed during the first iconic festival. For context, let's rewind one year back – to 1996. A peculiar detail of the Miensk club movement was that live electronic musicians simply did not participate in it for a long time. Drum Ecstasy played at a few parties, but that was far from regular occurrence. In the autumn of 1996, Safety Matches project stood next to the DJ for the first time in the Kisialoŭ House of Culture (later renamed into Sukno House of Culture on Matusevič Street), which created a precedent of electronic live acts playing at club events.

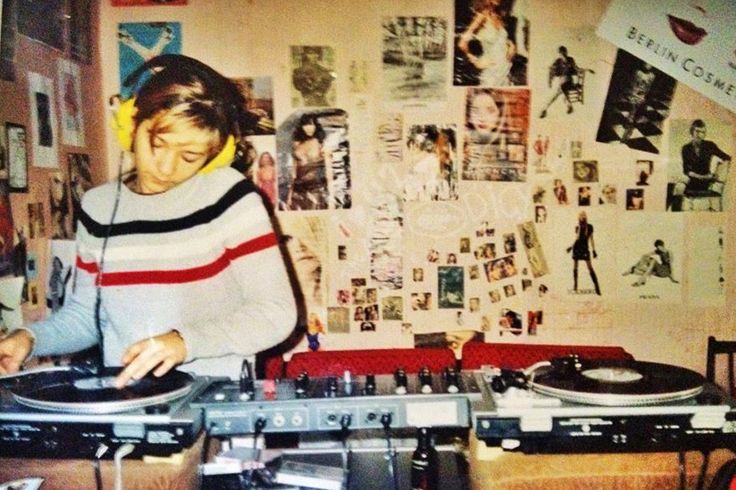

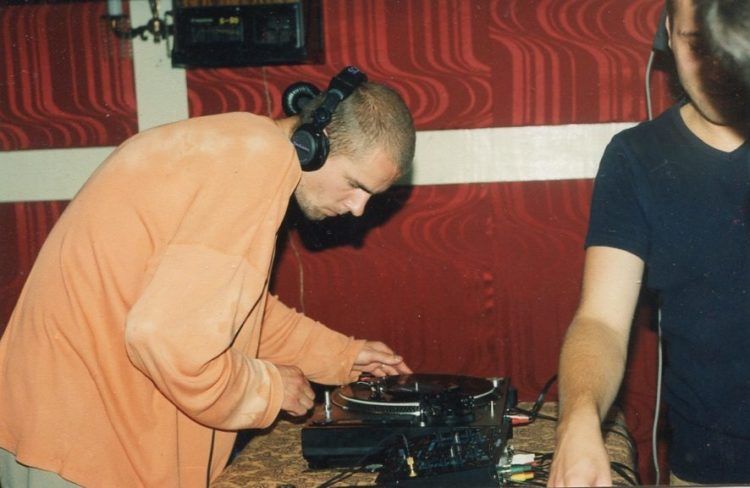

After the closing of Salut, the DJ scene found a new home at the Palace of Trade Unions. That is where some of the DJs, namely Yarik and Kon' first started regularly spinning vinyl. Digital archive of Muzykal'naya Gazeta articles reminds us of some interesting details from the dawn of the vinyl era in Belarus. Remember Yarik's tech savvy friend who built in pitch control resistors into his cassette decks that DJ I.F.U. played the first rave at the TV station on? Here our nameless hero makes an appearance again, retrofitting Yarik's soviet-era Vega turntables with the same type of mechanism, allowing the DJ to change the playback speed, which is necessary for beat-matching. The old turntables' torque was so weak, though, that he also decided to shave off a layer of metal from the platter and drill multiple holes in it in order to make it lighter. With this setup Yarik played his first vinyl set in Alternatyŭny Teatr.

– We put a pile of pillows under those turntables to isolate them from the vibrations, – recalls Kutuzov. – We also put Yarik's booth in the seats – away from the theater stage that served as the dancefloor and the speakers to minimize the feedback and the shaking.

<iframe width="100%" height="400" src="https://player-widget.mixcloud.com/widget/iframe/?feed=%2Fmagentalove%2Fdj-yarick-the-heat-ab-side%2F" frameborder="0" ></iframe>One of the first vinyl Djs was another Micia – Micia Ace. He was the first in Miensk to buy a pair of Technics turntables and a bunch of records. He encouraged Aleksei Kon’ to go vinyl by gifting him his first ten DJ records for start. There was a serious financial barrier for beginner DJs at the time: the records were expensive, money was tight, and having a basic collection made it easier to start as DJ.

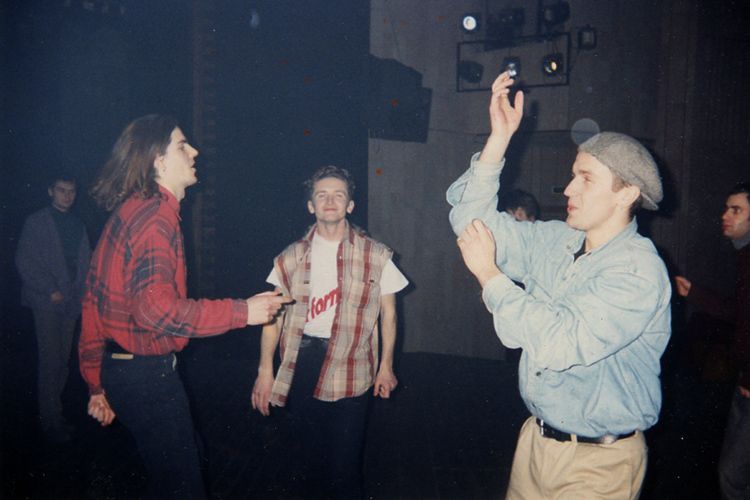

<h2>Pilot and Foreign DJs</h2>In early 1997, the Pilot Club opens in Miensk, setting a new standard for local nightlife. The new club was located in the Physical Education University in Viasnianka district of the capital. There was plenty of space, fluorescent lighting, great sound and a few bars. DJ Mitya has become its first resident.

– The club owners ordered 3,000 records from New York, – he recounts. – They arrived either by sea containers or by airplane, and then this guy from New York who they ordered them from came over himself. – The club announced a casting call for DJs. Mitya hesitated a little if he should participate, until his friends assured him he was cool enough to handle it. – I met Yarik there. And then this New York guy says: 'Ok, boys, get to it, I'll check it out. You can play back to back if you want.' Yarik and I got so into it that the guy was really impressed. He went to Paša Palonski, the club's director and said, 'These two guys play better than myself! I'd take both of them'. He was a DJ in New York too. That's how I and Yarik became Pilot's resident DJs.

<iframe width="100%" height="400" src="https://player-widget.mixcloud.com/widget/iframe/?feed=%2Fmagentalove%2Fdj-mitya-middle-frequency-2-ab-side%2F" frameborder="0" ></iframe>Yarik fell off after about a month to organize his own parties, while Mitya worked there for another year. Pilot club's other claim to fame was that they were the first place to bring over DJs from Russia. It was the place where known Russian DJs like Slon and Fonar' played their first sets in Belarus. Alaksiej Smit from Impedance Promo organized one of the first big events there in January 1997.

– We invited DJs from the cult Moscow club Ptyuch (and a famous lifestyle magazine – editor's note) – Kompas and Green, – says Alexi. – There was a huge turnout, over 700 people. At that time, it was really hard to believe that such tours could be a regular thing: foreign DJs had been to Miensk only a few times before – the Dutch DJs, who came as part of the cultural exchange a few years prior and a couple of Moscow DJ who played in Reaktor club. At that moment, it seemed like a beginning of a new era, and that Miensk would soon become an epicenter of club culture.

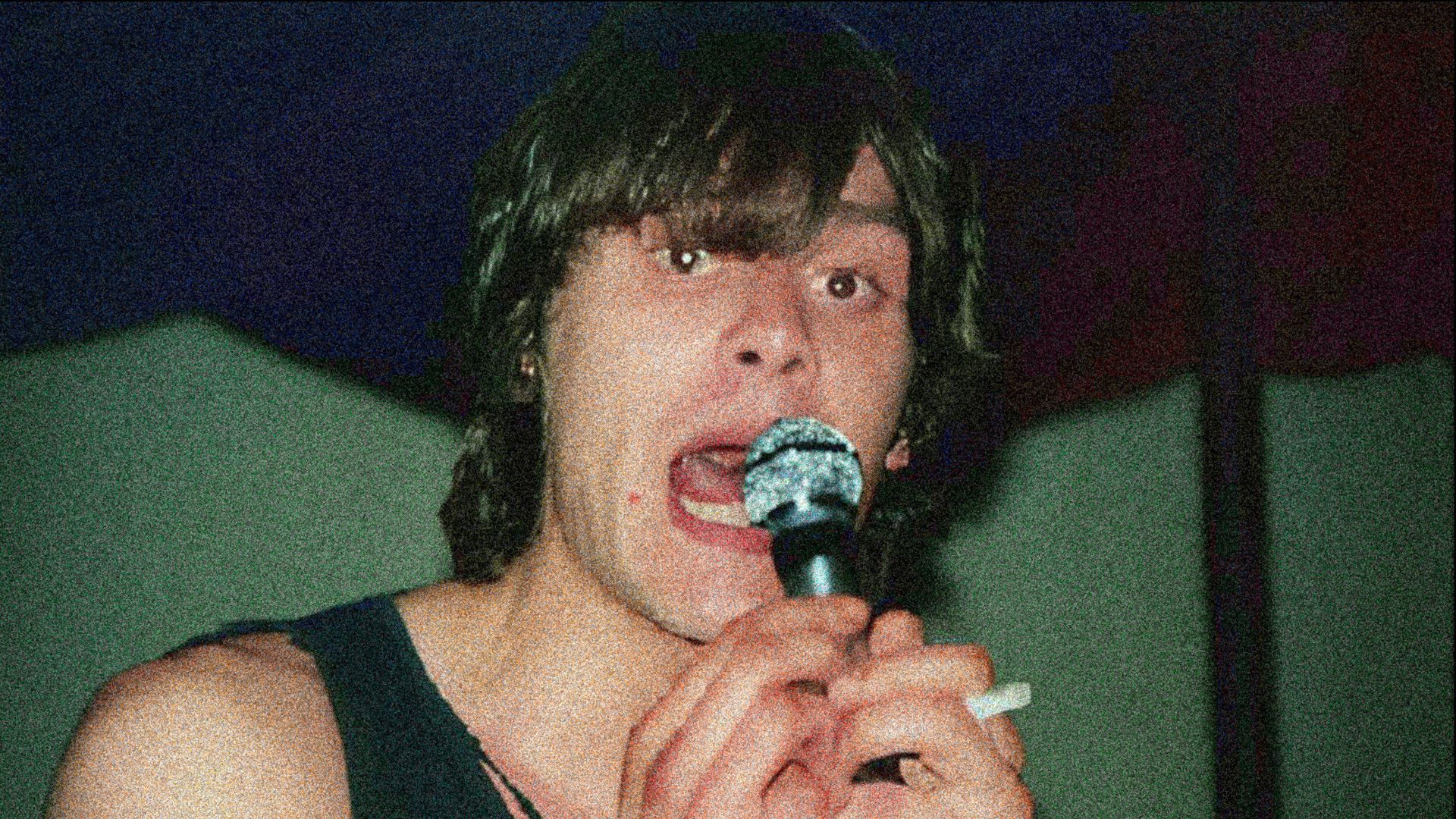

<h2>Sex Pistols Club – True Underground</h2>– Large-scale events with DJs from abroad quickly began to be perceived as mainstream, attracting fashionable crowds rather than true fans of electronic music. That's when the electronic music underground movement literally moved underground – to a small basement of a building opposite Horki Park, that was once home to Six Pistols punk club, and then became a secret venue for occasional illegal dance parties. Autism and Alex Coostoff performed there, as well as some foreign electronic live acts, that were radically far from the mainstream. Alexi Kutuzov recalls:

– Once we brought there a hardcore techno project from Poland called Kielce Terror Squad. Cops showed up that night and we had a hard time explaining what the three weird-looking Poles were doing in this basement and what that whole racket was.

<iframe width="560" height="415" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/DTO7vmHt6i4?si=HBZVTsByiMbITIgg" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" allowfullscreen></iframe>– My favorite and the most authentic place, – Dasha Pushkina shares her recollections. – I've never been to anything like this in any other city. The place worked as a party venue for, maybe, one summer. It smelled of damp, there were heating pipes running under the low ceiling, the floor was just dirt. But it was a club. With strobe lights and several UV lamps.

I remember one day we left there at 7 a.m. The sun was already shining, people walking dogs, first trams going on their routes. And all of a sudden, a bunch of wild-looking party people crash out of this basement. The humidity was so high inside that condensation was just dripping from the ceiling onto people all night. And we were dancing like we were working out too back in those days. And so I look around: everyone's black from waist down, because the dust has turned into dirt due to condensation, and we've been kneading this mud all night with our feet. Sweaty, dirty, but so happy! It was my favorite place, something completely unique.

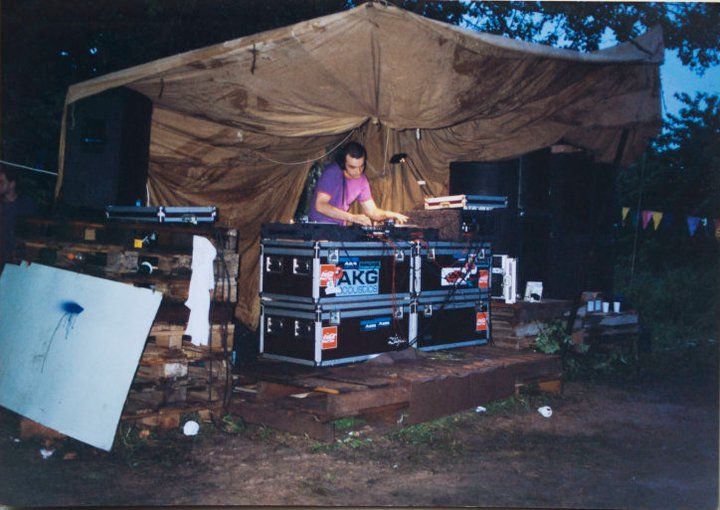

In the summer of 1997, the first open-air takes place in Miensk, called "Ravie Na Travie" (word play: "Ravie Na Travie" means "loudly sounds on grass", at the same time, "ravie" phonetically hints at "rave" – translator's note). Alena Barysik, its organizer and frequent partygoer at the time, an official Kazantip representative in Belarus, shares her memories about the event:

– A friend of mine Dzima Šylkin, who is now a professional bowler, ranked number 1 or 2 in the country, was then studying to become a physical education teacher. His friend Vital' worked at Liqui Moly, a spray-paint company. Together they decided to organize an open-air rave outside Miensk on the City Day. Through their sports connections, they found a tourist camp site on Pcič river near Miensk. On official celebrations days like this, all of police are in the city, all the attention is on the parade. And we were just out of town, with no one bothering us. There were about a hundred of us. We arrived with tents, everyone settled down at the campsite, then we constructed the dance floor. Liqui Moly donated a bunch of boxes of spray cans, so we covered the whole campsite in graffiti. After the party, we rested there until the next afternoon, and the next year we repeated it all once again.

In the following years, four more editions of "Ravie Na Travie" took place, and after that the commercial open-airs such as “Kosmos Nash” (Space is ours) and Global Gathering took over, but that is already history of the 2000s.

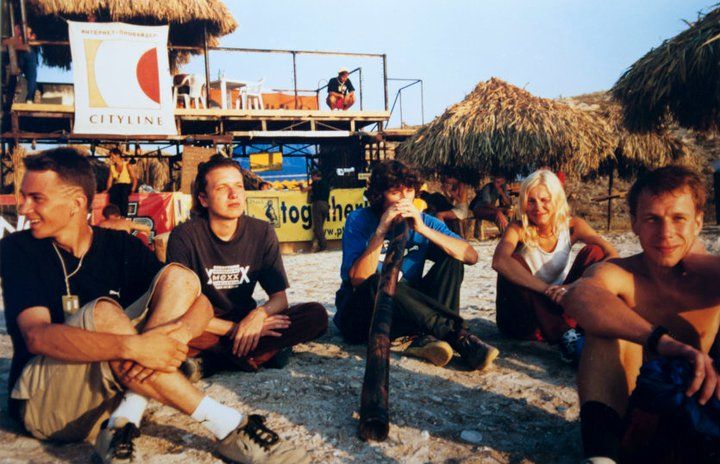

<h2>Kazantip: Towards the Wind</h2>In 1997, Miensk clubbers began organizing trips to Kazantip festival. Kazantip was a massive regional electronic music festival started in 1993 at Cape Kazantip on the Crimean Peninsula, Ukraine. Earliest editions of the festival featured dancefloors located in the abandoned nuclear reactor of the Crimean Atomic Energy Station. The festival, especially in those early days, was famous for the unique atmosphere of freedom that electronic music proclaimed from its very beginning. The festival united numerous urban electronic scenes in Ukraine, Belarus, Russia and the Baltic States, and later attracted the attention of an even wider audience. Alena Barysik recalls:

– Kazantip gave us a lot of friends. I learned about it in 1997 from Ptyuch magazine. My brother was vacationing in Crimea at the time, he brought me there in person just to make sure that this was a real thing. Because I arrived too early, even before the president of Kazantip Nikita Marshunok was there, it was feeling bored in the beginning. So I went around introducing myself to everyone I could find, offering help to the organizing committee. I ended up with the job of collecting info on local room rentals, so that people arriving could immediately find accommodation.

I had a lots of tapes with Kon' and Yarik's promo mixes, and I was giving them away to my new-found friends from Moscow. Then Nikita Marshunok offered me to become a representative of Kazantip in Belarus. When they advertised in Ptyuch, one of the contact phone numbers listed was mine. My parents took the messages, there was no answering machine back then, so they wrote down notes. They understood that it was an important thing for me.

After a while Saša Kosač started to organize bus-tours to Kazantip. Later on he would launch Kosmos Nash festival together with Vadzim Kudrašoŭ. And here's what Micia Hryšanaŭ recalls about the legendary festival:

– A crowd of party-goers, DJs and anyone who was up for it piled into a bus, paid 50 bucks for the round trip and that's how they went to Kazantip. If you were a DJ you could find someone to talk to about playing. The organizers gave every major city their own day: Moscow, Kazan', Kyiv, Miensk, etc. Back then, we were all at the peak of our DJing. Ptyuch magazine even wrote that Miensk had the best party day among all the cities.

<h2>Rezervacyja and Liveground Sound System</h2>Another landmark venue for the entire alternative movement of Miensk in the second half of the 90s was the Rezervacyja club (Reservation). It began in a place, that at first functioned as Piramida student disco at the Radio-Technical Institute dormitory located right behind the Riga supermarket. Later on, it became a venue for rock concerts before Denis London took over the artist management of the place. There are numerous media accounts of the club's events out there. We can also recommend the book "Ot Panikovki do Shajby: Gajd po tusovocnomu Minsku" (From Panikovka to Shajba: A Guide to Party Miensk) by Paval Valatovič and Alaksiej Kavalioŭ, that recounts stories about various Miensk hangout spots of the 90s, from very punk-rock to totally glamorous ones. Let's check out what our protagonists have to say about the place from the electronic music perspective.

– The club was great because it was a breeding ground for the alternative community, – says Alexi Kutuzov. – Rezervacyja was open every day. Many of the Belarusian bands started out here, like Leprikonsy for example. Bands from Ukraine and Russia were frequent guests as well. We all organized electronic parties there: I did with my newly-created Liveground Sound System project, Yarik and Kon' had their parties there too, as well as DJ Commanda Labella. When the Oxidiser.net forum appeared, they also did their parties there for a while. Then the club was renamed from the Rezervacyja to the A-Klub, but, in fact, all the employees remained in place, including Denis London.

The club was an interesting melting pot, because it gathered the most diverse crowds at its concerts and parties: ravers, punks, rockers, metalheads, alternative kids, etc. Kutuzov admits that during his frequent visits to the club he had a chance to make acquaintances with the entire alternative music milieu of the city.

After the readers of state-run Narodnaja Hazeta (People's newspaper) complained about the club to the newspaper calling Rezervacyja a drug den, an inspection shot it down. After that shutdown, Rezervacyja went through several reincarnations. Immediately after, the club re-opened as Alternativa, then as simply A-Klub, with the same art-director Denis London at the helm, which is why the unstifled spirit of freedom and creativity carried on despite the name changes. Once A-Klub closed down for good, Denis assumed similar role in the newly-opened club Baza on Broŭki Street. In the early 2000s he found himself in NC club on Kastryčnickaja Street – a location that would go on to become the epicenter of hipster gentrification of the capital in the following decade. But, let's go back to the late 90s.

In 1999, Alexi Kutuzov, along with his friend Paša Košaleŭ, organize the Liveground Sound System promo-group, which included 10 people from various creative fields – DJs, musicians, designers:

– We all agreed that a lot of the promo groups that have appeared are just making money and treating nightlife as a business, while we wanted to represent the underground in all its manifestations and play interesting experimental music. On the musical front I was backed by Energun, Andy Dust, DJ Filter who had a top-notch electro record collection, there was also DJ Spy who played deep, dubbed-out, almost chill-out techno. I myself had a large collection of drum'n'bass, electro, breakbeat, electronic and ambient records. We organized Liveground Sound System parties in A-Klub, as well as tours around Belarus: Homiel, Horadnia, Viciebsk.

<h2>Touring</h2>Although this series of publications is devoted to the history of the Miensk electronic scene, we have to at the very least mention the scenes in other Belarusian cities.

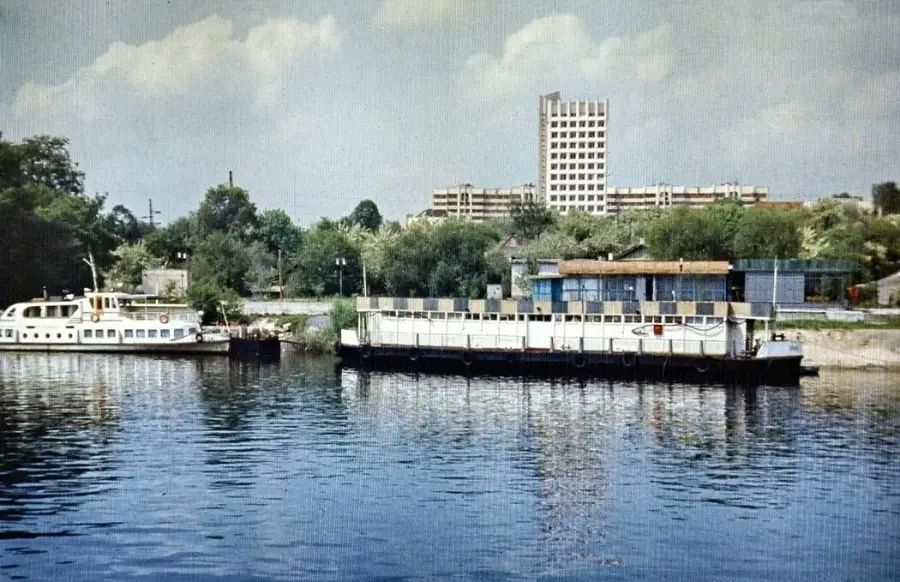

Homiel became the next city after the capital to pick up electronic music baton. First events in the city date back to 1996. The parties were organized by Slava Vavutkin, a.k.a. Slava Unkle. Homiel was also home to now legendary DJ Ko100fei, who, by the way, was also part of the Liveground Sound System crew. "He later moved in with me to live in Minsk, and we did parties together," says Kutuzov. "He has an excellent musical taste, and he still actively plays in Homiel. We organized a few drum'n'bass and techno events on a ship on the Sož river together. It glided so smoothly on the river, the needles didn't skip once on the records."

After Homiel, electronic music events started in Horadnia and Viciebsk, and later on in Bieraście. Liveground Sound System were organizing not only DJ parties, but also actively invited live projects, for example, STREFF – a dubcore band started by Mikita Chudizakoŭ and Dźmitryj Pratasievič from Elements Of Sci-Fi, later on Dźmitryj was replaced by Mikita's wife Sviatłana Šlachava.

– At first there was no connection between the cities, – Mikita Chudizakoŭ recalls. – Miensk was on its own, and other cities were on their own. Then, as I was working for a newspaper, I was contacted by some guys from Horadnia who were also interested in electronic music. They had connections in a local House of Culture or a club and wanted to organize an electronic music party there. And in the spring of 1998, the Rave Around the Clock festival was held there. The local guys were responsible for the organization, and I was responsible for the musical part. Myself, Dzima Pratasievič, I think Alex Coostoff, the guys from Energun – we all went together, and those Horadnia organizer guys had a musical project of their own too. I think I even wrote a review of that event in Muzykal'naya Gazeta.

Liveground Sound System also organized mini-tours of Belarus for local electronic musicians. Mikita Chudizakoŭ continues:

– We played in Bieraście, Homiel, Horadnia and other cities. It was a memorable experience, because it was the end of the 90s, the atmosphere was often unique. For example, in a club in Bieraście, there were reserved seating areas with vodka bottles on tables, as we played digital hardcore and techno. Fun times!

Despite all the shortcomings and difficulties, our events attracted many positive people who came specifically for the new music and the new ideas. It was always nice to see their eyes light up because they wanted to experience something new. Such people are a minority in our society, however, there was no shortage of enthusiastic open-minded young people at our events, and at electronic music events in general back in the day. That in itself was a very powerful motivator for us!

Miensk DJs' and electronic musicians' tours were not limited to Belarusian cities. In previous episodes we mentioned cultural exchange programs with Dutch artists. Alexi Kutuzov shared a little more insight about the creative exchanges that happened at the time:

– DJ Yarik was the first Belarusian DJ to play in Europe. We went to visit my Dutch friend who had a gabba hardcore soundsystem and who was organizing a party in the Berlin art-squat Tacheles. So we managed to get Yarik booked there. Of course, he had the 'lightest' variety of techno played that night, compared to the Dutch and German DJs on the line-up. Those guys unscrewed some screw in the turntables to make the pitch go up to +15% instead of the standard +8% so they could have the records play even faster. Yarik played warmup as a newcomer, but it was still a cool achievement to have played in a Berlin club in 1997.

In August 1998, echoes of the Russian economic crisis reach Belarus. Not that local economy was particularly stable before it, but the financial turmoil of our eastern neighbor added a particular urgency to financial matters. Vadim Militsin shares how the financial crisis affected his family's situation and prompted him to consider emigration:

– Suddenly, I realized that survival was becoming a struggle. Buying fruit and bananas felt like a celebration. When my wife's mother called to tell us that they had started preparing documents for us to move (to USA – editor's note) – and up until then, I had been resisting – I finally agreed. The 1998 crisis completely shattered me. Before that, it felt like things were gradually improving, like there was still hope to fix everything. But in that moment, something inside me broke.

Alaksiej Smit, who was an event organizer at the time, shares his insight on this matter:

– Weird things started happening to our economy. After the Russian crisis in August '98, the income level in Belarus also fell significantly. The students' monthly living allowances (unlike student scholarships for the select few in the West, stipendiya in ex-USSR is paid by the universities to the top half of their students – translator’s note) at that time were about 4-5 U.S. Dollars. Weirdness with the currency exchange rates. It was making less and less sense to work legally, and organizing larger-scale events illegally was an equivalent of punching a cop.

Micia Hryšanaŭ has his own perspective on those times:

– In my opinion, the crisis has had a greater impact on businesses and people who made a lot of money. Of course, we all felt some impact, but I wouldn't say we were deeply affected by the economic downturn. If you have no money, you have nothing to lose. People involved in electronic music basically did not make any money from it at that point, so nothing much changed for us.

One way or another, the crisis, along with changes in the political climate, became one of the factors that influenced the transformation of the electronic scene in Miensk. And the main feature of this transformation was the washing out of key figures from the scene. Some of our heroes were attracted to other cities: for example, Yarik was invited to the Moscow club Territoriya, Kon' moved to Kiev, where he made an illustrious DJ career, Dasha Pushkina was easier to catch in St. Petersburg and Moscow clubs than in her hometown Miensk. Some moved to the West, like Vadim Militsin (New York), Mikita Chudizkoŭ (Belgium) and Alexi Kutuzov, who relocated to London in 2001. Some took the path of 'inward migration' shutting off from the world to devote most of their time to music, like Graf. DJ Mitya put DJing on the backburner. Claus, unfortunately, passed away.

This washout occurred in a fairly short period of time. Turn of the century season 2000-2001 marks a drastic break that disrupted the continuity of the scene. You can even say the scene never recovered from it, instead a completely new scene had to emerge – with new people filling the void and carrying the electronic nightlife baton into the 21st century. A scene that was no less interesting and cool, but different.

This is, sadly, very characteristic of Belarusian culture in general: every once in a while the cultural memory is all but completely wiped out, new heroes emerge over time and consider themselves pioneers, as if nothing existed before them. But that is not the truth! Our history is actually very rich in events, heroes, values and ideals. The history of Miensk electronic scene of the 90s is but one of the testaments to that. Hopefully, the podcast “Ikarus: Stories of Electronic Music in Belarus” and its text versions will contribute to preserving the memory of our history and the people who create it.

Check out the podcast on Spotify, SoundCloud and Apple Podcasts

Translation into English by Alik Khomiak, artwork by Yana Zenovitch